Introduction

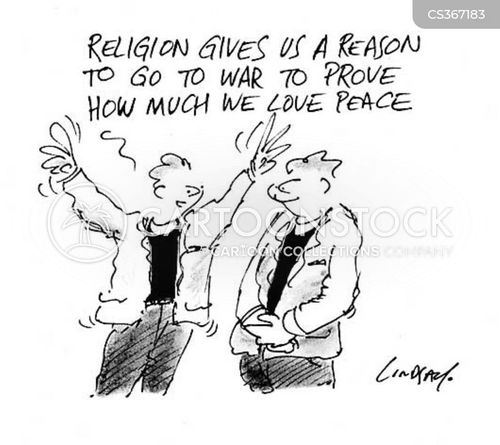

The ethics of peace and war, especially in the current times has become a highly popular topic of contention. The debate on how to perpetuate peace–whether this be through violence (and therefore wars) or through pacifism, is an issue that is widely debated and has yet to be resolved. This was a topic that was also heavily debated in our online class forum, as some people seemed to think that pacifism, although seemingly nice in theory, is impossible to emulate given the circumstances of war. One of the most intriguing arguments made in particular by one of my classmates was that war is not morally equivalent on both sides, and so violence/fighting is not completely ‘evil’ as it can be a means to an end. The example that this classmate gave was that of Christians who participated in World War I, who did not believe in the concept of taking another person’s life, still participated in non-combat roles, still helping in the war, without compromising on their values.

However, I believe differently. I personally think that despite war not being morally equivalent on both sides (as some can take part in having some level of basic human decency), both sides are still morally culpable to some degree. But even with the World War I example, fighting was only a temporary fix. Germany was still disappointed with their defeat and was still wanting more, and so the events lead up to World War II. The fighting during World War II didn’t necessarily end there, and relations/tensions between different countries and ideas of communism versus democracy came about, and throughout the 1900-present day, we have had a long string of various different wars (which did not necessarily all cause each other) but in which fighting/engaging in wars was never really a permanent solution. In some cases, war did help in subduing certain Great Powers (such as Germany and later Russia–to a certain degree) however, it was also other factors that would lead to treaties. So my point is that it may be premature to judge modern day pacifism as a totally realistic way of handling the evils in the world, but it still is possible, however, just not with the current system of international relations that we now have. With that being said, now I will discuss what the Bible’s thoughts on pacifism/war are.

Biblical Perspective

I think that one important source to consider when deliberating on the foundations of violence and just war is one of the oldest traditions; the bible. In chapter 14 of The Moral Vision of the New Testament, Richard Hays questions the compatibility of partaking in violent wars and Christianity. Hays states:

“It may be seen as a sad duty; the church may lament as well as celebrate its dead soldiers. Rarely, however, has the church fundamentally questioned whether military service is consistent with Christian service…Is it appropriate for those who profess to be followers of this gentle shepherd to take up lethal weapons against enemies?”

Hays 317

Essentially, would it be considered the will of God to take up armistice in service of justice? Would it ever be considered just to employ the use of violence as a follower of Jesus? One key text from the Bible to consider is Mathew 5:38-48. In this section, Mathew discusses the importance of not acting in revenge. He states:

““You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven.”

Mathew 43

Even in this mini excerpt, we can see that Mathew takes the concept of ‘loving your neighbor’ to the next level; this applying to love your enemies as well. In this case, it can be inferred that rather than striking the ‘evil doer’ with violence (even if it was in pursuit of justice) it is still not right to act violently but rather lovingly. So if the Bible mainly seems to perpetuate this idea, then how exactly have we been able to justify war? Hays adds to this conversation by stating,

“The New Testament contains important texts that seem to suggest that this question must be answered in the negative, but human experience presents us over and over with situations that appear to require violent action to oppose evil.”

Hays 317-318

In this case, Hays seems to imply that war and the ethics of war cannot be something that is possible to be ever condoned by the Bible, but rather, through the experience of being humans itself, war/violent means will always be imminent.

Aurelius’s Perspective

However, we still haven’t quite answered the main question; how exactly do we justify acts of violence in the defense of justice? In order to delve deeper into this question, let’s consider Marcus Aurelius’s thoughts on the topic. Aurelius, in a simialar manner of Mathew, believes that any act of injustice fulfilling purposes of self-indulgance, or necessarily revenge, is unjust as it divulges from the true nature of human beings. Aurelius states in Book 11,

“Any movement towards acts of injustice or self-indulgence, to anger, pain or fear is nothing less than apostasy from nature. Further, whenever the directing mind feels resentment at any happening, that too is desertion of its proper post. It was constituted not only for justice to men but no less for the reverence and service of god — this also a form of fellowship, perhaps yet more important than the operation of justice.”

Aurelius 112

Essentially, Aurelius, in contrast to Hays, finds any act toward fear, pain, self-indulgence, or anger to be against the nature of the rational human being. Since what much of war boils down to these four categories, he would not be condoning war in this sense. Especially when referring back to the example of World War I, since it was essentially perpetuated by Germany’s fear of a rising Russia, and it’s desire to expand and grow as a central world power (fulfilling two of the categories–fear and self-indulgence) World War I would not be condoned. The other countries (Great Britain, France, and Russia–later the US) would not necessarily be condoned in taking part in the war by this standard because it could be argued that they partook in war due to fear of a rising Germany. However, this logic doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense. How is it that the other countries war against a rising Germany be seen as unjust? Aurelius answers this question. Aurelius states

“Judgement vary of the whole range of various things taken by the majority to be good in one way or another, but only one category commands a universal judgement, and that is the good of the community. It follows that the aim we should set ourselves is a social aim, the benefit of our fellow citizens. A man directing all his own impulses to this end will be consistent in all his actions, and therefore the same man throughout.”

Aurelius 112

Therefore, since Aurelius argues for the justice in acting for the sake of the cosmopolis, or the community, the fighting done by the triple entente, and later the allies in World War II can be justified as they served in the war for the benefit of all life and to serve the purpose of the safety of the world as a whole. In this way, the actions of Great Britain, France, Russia, and later the US can be justified as long as their participation can be seen as consistent with the good of the overall international community.

Final Thoughts:

In this post, I went over the different perspectives on the question of the justification of war/violent means. Even though I still believe that pacifism is still entirely possible, it still cannot always be the answer; similarly, violence cannot always be the answer. In the following blog posts, I plan to explore more on the ideas of acting justly as well as acting in the interest of the cosmopolis.